Pakistani governments have always believed that all they need to do is change the narrative about Pakistan, without changing its reality. The reality is that extremism is the biggest threat facing Pakistan, both domestically and in the international arena.

In a recent piece, security analyst and author of books on Pakistani jihadi groups, Muhammad Amir Rana noted that while for many Pakistanis the death of Khadim Hussain Rizvi may appear to be “the beginning of the end for the TLP”, it “would be unwise to underestimate the power of the TLP narrative.”

According to Rana, “The TLP under Rizvi has been an amalgamation of charisma and religious narrative; the organisation has eagerly wanted power either through entry into the corridors of authority or recognition of the influence of its religious zeal and street power on politico-ideological and policy matters. However, it is not the first organisation with hard-line, religiously inspired motives and ambitions to have emerged. There are at least 247 religious groups and parties operating in the country that have more or less similar motives and agendas. The inception phases of many of these groups have also been similar; they largely grew from either the Khatm-i-Nabuwwat movements of the 1960s and 1970s or sectarian groups’ campaigns of the early 1980s, which deepened the sectarian divide in society. These groups also had firebrand leaders who nurtured religious narratives, and the TLP has banked upon the same ideological arguments.”

As Rana notes, “Since the establishment of Pakistan, each decade has seen different religious groups that have hedged or amplified religious-ideological sensitivities around various issues. But the finality and honour of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) have remained the most important themes for sensitising the people. The TLP, however, organised aggressive street protests and choked federal and provincial capitals. In recent history, the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) led violent protests in 1989 over the issue of Salman Rushdie’s blasphemous novel. From 2005 to 2012, it was the banned Jamaatud Dawa which mobilised and brought together religious organisations under the banner of the Tehreek-i-Tahaffuz-i-Hurmat-i-Rasool over the issue of the blasphemous images of the Prophet published in different European countries. The Barelvi parties remained very instrumental in all these campaigns mainly in Karachi and Lahore. In Karachi, it was the Sunni Tehreek that led such protests and in Lahore several small Barelvi parties remained part of the JuD-led alliance.”

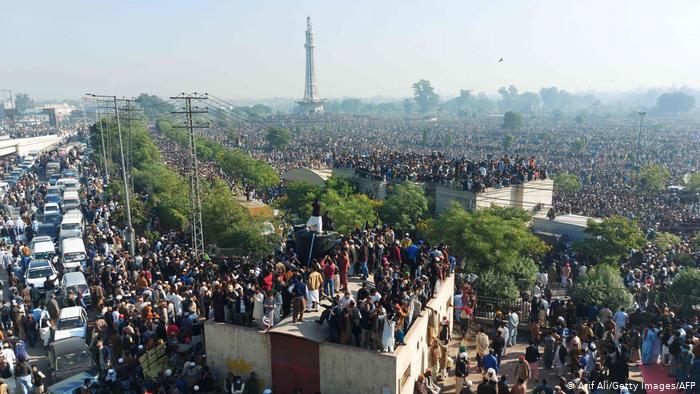

Further, “A report has been doing rounds in the media that the TLP is facing an internal leadership crisis and the nomination of its new head Saad Rizvi, the son of Khadim Rizvi, has been challenged by some senior members of the party and by others who have left the organisation. Such divisions among religious groups are not a new phenomenon. Many groups split over the issue of leadership and control over financial resources. The TLP will need someone to follow in Rizvi’s footsteps for exploiting the religious narrative and attracting crowds, which may also keep the party’s rank and file united. But whether or not the TLP succeeds in maintaining its unity, it will be a huge challenge for the new leaders to keep the firebrand legacy of Khadim Rizvi going. At another level, while there are several contenders within the Barelvi school of thought, other sects are also waiting to replace the TLP. The followers of the other sects, including those he had issued statements and fatwas against, also attended the funeral of Rizvi. The reason was the narrative, which Rizvi made attractive through his fiery sermons.”

Finally, as Rana notes, “another issue remains crucial and this is about the state’s inability to deal with such groups. State institutions have sympathy for all sorts of religious groups, except when they start challenging their turf. The TLP had been testing the nerves of state institutions for a long time and the state adopted its conventional approach of appeasement and pressure whenever TLP supporters came out onto the streets. The disadvantage of the approach is that religious groups seek legitimacy and political power whenever the state makes an agreement with them. Khadim Rizvi had made a deal with the government just a week before his death, which was a big gain for his party, though the government had denied that it is bound to follow the agreement. Such commitment gives the impression that the state institutions are not capable of chalking out a long-term strategy to deal with such groups for whom they may have some other political utility.”

![]()