Pakistan’s history has demonstrated that the people of the country, like their neighbors, crave democracy. They vote in elections, support civilian political parties, and participate in the democratic process. Yet, time and again, they are disappointed.

The Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) has given hope to many people inside Pakistan. It is often difficult for such a large coalition of ideologically diverse political parties to stick to one agenda. While the PDM is still viewed as a threat by the establishment, there are internal fissures within the movement that may create long-term problems.

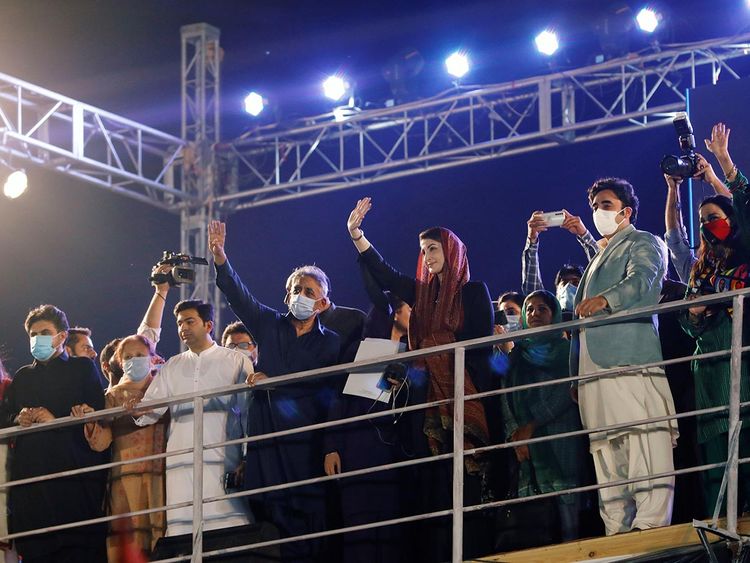

In a new piece, Aasim Sajjad Akhtar undertakes a detailed scrutiny of the 11-party coalition. “For a few weeks in the autumn, Nawaz Sharif’s fiery speeches from London’s comfortable confines had even the most seasoned observers suggesting that Pakistan’s polity was on the cusp of an epochal transformation. Some pronounced that the age-old establishment-centric script of Pakistani politics was being rewritten, once and for all.”

He argues that the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) “took up the scandal of enforced disappearances and criminalisation of political dissidents. It invited revisionist takes on Pakistan’s ‘official’ history, vociferously challenging the refrain of ‘traitor’ that has been employed against figures like Sheikh Mujib, Bacha Khan, G.M. Syed and virtually every major Baloch political leader since Partition. But a rip-roaring debut has given way to talk of fissures amongst the parties that make up the alliance, and whether big players really want to confront the establishment, or are seeking only a piece of the proverbial pie.”

Akhtar notes that the PDM’s “initial narrative stood out not necessarily because it targeted the ‘selectors’. More significant was the spectacle of a three-time Punjabi prime minister at least partially debunking the very official ideologies that have facilitated the steady militarisation of state, society and economy.”

Finally, Akhtar remarks “mainstream parties’ stunted economic, political and ideological horizons set the stage for Pakistan’s hybrid regime in the first place. So long as invoking domestic and foreign ‘enemies’ is our ‘normal’, expect Pakistan’s tryst with praetorianism to continue unabated.”

![]()